The Ballad of Christophe Bassons

What One Honest Cyclist Tells Us About Integrity and Power

As I write this, I have half an eye on the TV for arguably the greatest sporting spectacle on earth – the Tour De France. 180 or so athletes are locked in a contest that is absurd in its brutality: searing heat, gruelling mountains and day after day of intense racing. I have been obsessed with it since childhood.

I am not sure what it is about the Tour that captured my imagination. The epic scale was one thing. I enjoyed the meandering commentary, which spiced up some of the duller bits of racing with snippets of French history and geography. I was also fascinated by the exotic range of team and cyclist names, from the German efficiency of Deutsche Telekom to the almost magical sounding Uzbek sprinter Djamolidine Abdoujaparov. Most of all, I suspect, it was something my father was into, and that hour by the TV became a stalwart of a summer routine.

Naturally, as a young boy, the indefatigable champions became my heroes. The almost unbeatable Spaniard, Miguel Induráin, the eccentric Italian, Marco "The Pirate" Pantani, and the cool and collected German Jan Ullrich. Each had a place in the pantheon. At the pinnacle, however, was Lance Armstrong. He was the one-man miracle who first defied death in his recovery from cancer, and then the odds, not just to return to cycling, but to become the greatest champion the Tour had ever known. For a young lad, these were men you couldn't help but admire.

Of course, if you know anything about cycling, you know where this leads. Each of these men was a fraud. They cheated. They lied about it. They not only succumbed to the systemic corruption of the sport but actively propagated it. Armstrong was not the greatest of all, but the worst. The man who had the hubris to stand on the podium and say to the sceptics, "I'm sorry you can't dream big and I'm sorry you don't believe in miracles", perpetuated one of the greatest frauds in sport. He didn't just dope, but built an entire cheating infrastructure, browbeating anyone who dared look for honesty in the sport.

It was galling to see one's heroes so diminished. To have grown up believing in people and to watch the same pattern repeated. The victories, followed by denials, investigations and, eventually, full confessions. Perhaps it was a salutary lesson. About whom to believe, when to question, and not getting carried away with a narrative just because you want it to be true. Eventually, it led to realising the real message of heroism that lay in a figure often forgotten by the sport.

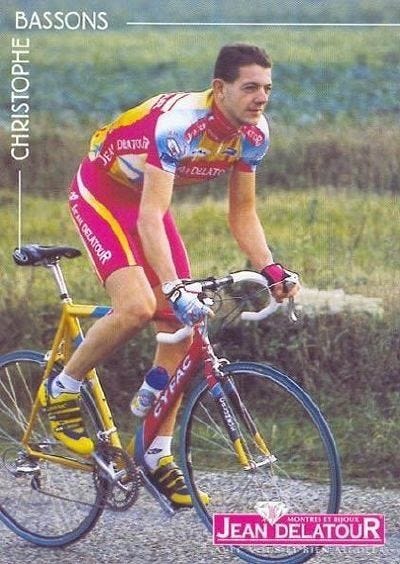

In those days of the late 90s and early 2000s, Christophe Bassons was an unlikely sporting hero. He was never particularly successful. He kicked around the peloton for just five years, picking up a few wins but never anything on the Grand Tours. On paper, he was nothing more than a journeyman, one of sports' many names who perform at a level few humans can, but are eclipsed by those who go a little bit further or a little bit faster. Yet really, he is one of the few cyclists of that era worthy of remembering.

The reason his career faltered was not simply his results. It was his strident honesty and refusal to fall into the temptation that those around him so readily succumbed to. In 1998, he was on the Festina team, the one which kick-started cycling's biggest scandal when their soigneur (a sort of team assistant) was stopped by customs officers with a haul of performance-enhancing drugs in his car. The team was disgraced, purged from the race, and all but one of its riders arrested. In the midst of corruption, Bassons was clean.

As the scandal developed, he was revealed as a beacon of propriety. His other riders attested that he had no part in the team's doping programme. It later emerged he had turned down a contract from Festina that would have paid him 270,000 francs a month if he doped – a 10-fold increase from the meagre wages of a team junior. He not only continued to ride clean but drew attention to the endemic level of cheating among the men around him. He wrote columns for the French press highlighting suspicious results and practices within the peloton. Bassons' honesty won him neither races nor friends.

For his fellow cyclists, he was a traitor. Refusing to cheat and -worse- talking about it made him a pariah. His teammates refused to talk to him and cut him out of the traditional way prize money was shared around. In races, he'd be spat on and jostled by those who resented the "betrayal" of his honesty. Chief among them was Armstrong. Leading the Tour de France makes you the unofficial union leader of cyclists, and Lance used this to police the code of silence around cheating brutally. In one race, when Bassons attacked, Armstrong chased him down and berated him, telling him he should quit cycling for the good of the sport.

This cracked Bassons. The psychological pressure of being one of the few honest men in cycling was too much. With almost the entirety of the sport against him, he realised he would either have to get on board with the cheating or leave. He chose the latter, walking away from the team hotel at five-thirty in the morning. He'd never ride the Tour again, and when the bullying continued in minor races, he left the sport entirely. After six years in the peloton, Bassons found a new career as a sports teacher and administrator. He had barely been a footnote in the annals of professional cycling.

A decade later, he was, of course, vindicated. The Armstrong edifice came crashing down. The greatest story in sport was, in fact, its greatest scandal. And the tale of Bassons, and the honest men like him who were discarded by the sport, were perhaps its biggest victims. After all, while you can argue that Armstrong mostly beat people who, like him, were cheating, those who chose to be clean never even got close to the podium. The wholesale corruption of the sport squeezed out any chance for the honest. The tolerance for cheating effectively made it mandatory, unless you were prepared to walk away.

That is what makes Bassons and the few like him so admirable and fascinating. The sad reality is that there was every reason to cheat. It is easy to understand why it happened. If you were a young man who had dedicated your life to the insane suffering of long-distance road races, a bent tilt at glory made more sense than giving it all up for moral purity. Everyone else was doing it, you'd probably never get caught. Cheating might win you fame and fortune, and it would at least keep you among the decent earners in a sport you have thrown everything into. It would also keep you on speaking terms with the rest of the peloton.

When you look at those conditions, it is easy to see why people cheated. It is almost baffling that they wouldn't. Dishonesty had become the default, the path of least resistance. As with many scandals, those involved could concoct a rationale that excused their behaviour. While a few ringleaders concocted elaborate schemes and enforced obedience down the peloton, the others acquiesced. Told themselves that such compromises were necessary, that there was some honour in the loyalty of the code of silence, twisting or just ignoring the morality of it all.

The fascinating question is not why so many cheated, but why some like Bassons chose not to. They deserve our praise and admiration, but also more examination. About what in them made them different and made them take a stand. Lots of organisations suffer from the same problems as the drug-riddled peloton, where misconduct has become normalised and enabling it rather than challenging it has become a sign of loyalty. We've seen it in state bodies a lot over the past few years, but it is a huge risk in the private sector too. Frauds like Theranos or the opioid scandal have often only unravelled when people like Bassons have found the strength to go against the grain.

There is no redemptive arc in the story of Christoph Bassons. In a sport that prizes suffering above all else, the moments of glory went to those who were weaker than he was. While they were ultimately disgraced, much about them endures. An early investment in Uber means Armstrong remains hugely wealthy, despite his former sponsors clawing back much of the money they gave them. Bassons himself is remarkably unbothered by this. In his occasional media appearances, he is content with the life he built away from cycling, and seemingly holds little ill will towards those who cheated and abused him. It is another aspect of his character to admire.

This is perhaps the biggest reason why his story matters. It reminds us of the cost of doing the right thing, that it often leads to ignominy and anonymity. That it often achieves little, after all, it is hard to swear that cycling is now clean, and many other sports have failed to even acknowledge their demons around this. For a few men, however, doing the right thing was always more valuable than any other reward. It is that we should take from this story and the thought of how and when we might have to emulate them, and how we can encourage others to do so too.

Bassons' story is not one of triumph, but of refusal. He didn't conquer the mountains, he didn't beat the clock—but he didn't give in. In a world that punishes virtue and rewards silence, that alone is remarkable. We celebrate winners, but we learn more from those who walk away. And in a culture where compromise is often the cost of success, the quiet example of someone who said "no" might be the most important legacy of all.

And now, something else:

My picks from around the web this week: