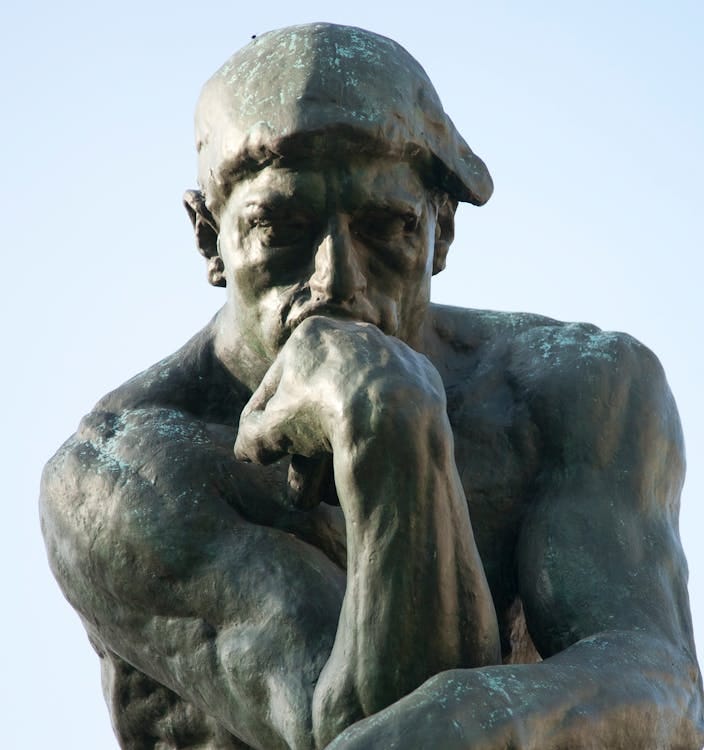

Why can't the English teach their politicians how to think?

How warped incentives are shallowing out our discourse

Keir Starmer has so far made one memorable speech as Prime Minister. It was a regrettable one. It was, indeed, one he himself regretted – later distancing himself from his own rhetoric and turns of phrase. It points to a paucity of advocacy, but one which is hardly unique. There have been a few memorable speeches in recent years, or from recent politicians. Even our most noted politicians have failed to land oratorical points. Farage is not known for anything he has said, while Johnson’s “famous” oratory is a few choice phrases among what are often incoherent ramblings.

This has not always been the case. In 2009, Hansard celebrated its centenary by asking various notables to curate a volume of the best addresses from that period. It makes for remarkable reading. Some are well known – Howe’s resignation, Powell on Hola, Cook on Iraq – others (and their authors) have been lost to the public imagination. Yet each is worth reading. Many are rhetorically deft, but the greatness comes not from the fluidity of their prose, but the clarity of their thinking. Arguments are crafted in long form: the thinking is clearly tested; the issues are fully explored with focus and principle. In short, no accidentally saying something you later retract.

This is a skill that is now often absent in our politicians. Speeches, especially in the Commons, tend to be forgettable (Tom Tugendhat, on Afghanistan, perhaps a notable exception). Politicians’ writings are focused on banality. Lawmakers seem afraid to show the sort of intellectualism that was once commonplace. They rarely talk openly about ideas – or try to communicate complexity and nuance. The new populists are worse for this, but many are following their lead, making remarks they have clearly not thoroughly thought through or followed to their logical conclusions. This is noticeable not just in their oratory but also in their broader engagement with issues; not just a paucity of rhetoric, but the language that lies behind it.

It is easy to assume politicians have just got worse. It’s a common argument that the Westminster talent pool is shallower, a result of worsening conditions for MPs. But like many common arguments, it’s essentially wrong. Our current parliament probably has the highest levels of formal education ever. The 2024 intake was perhaps better versed in policy than any of their predecessors. Indeed, many of them have the same credentials as those we praise from the past. Starmer himself has the BCL, arguably the most competitive and impressive post-grad qualification in the land and decades at the Bar behind him – precisely the sort of thing those smart MPs of the mid-century racked up. Something else is going wrong.

The shift is not one of ability, but of expectation and incentives. Nothing is encouraging our politicians to think deeply or argue intellectually. There is often much pushing against it. Incentives build culture, and that dictates behaviour. Politicians adapt to this, just as anyone would. As a result, they are pulled away from the types of thinking they are obviously capable of, to the vacuous and the quick. When this happens, perhaps it does make it easier for those who lack depth to rise, but that is the consequence, rather than the cause.

We primarily see this through the media. The great irony of 24-hour news is that this time is devoted to rapid-fire, attention-grabbing hits rather than in-depth exploration. Politicians on TV are hit with rapid questions and trained to deflect them. It has become a game about scoring points, getting gotchas, and surviving a media round without making a fool of yourself. Questions are superficial, answers often too. No one is creating a space for nuanced debate – and usually any nod towards it is taken as weakness.

Social media exacerbates this. The push towards post-literate politics condenses minutes of discussion into clips of a few seconds. Political communication, in turn, is shaped by this. Commons speeches are crafted not to convey an idea or to delve into the nuances of an issue, but for twenty seconds or so to be served up on Twitter and TikTok. The politicians who do this well are the ones who get lauded and promoted, with likes and shares serving as an easily measurable metric that “thoughtfulness” cannot. The whole media conspires in this, effectively making for an intellectual race to the bottom. Politicians who look for complexity or acknowledge the challenges in their arguments are sidelined. You usually get further by posting the party line than by interrogating it. So even those capable of it elect not to.

This differs massively from the environments in which older politicians were both brought up and operated. The papers of the past were far more intellectual in their pursuits and prose. So too was the BBC under its Reithian directives. Politicians and voters themselves tended to be steeped in at least one of two things – classics and church – which encouraged deep thinking about what you were saying and how you said it. Both bred habitual mental exercises of rhetoric and reasoning, and while one was primarily reserved for the well-off, the second was universal. Indeed, the connections of the non-conformist churches to the labour movement helped boost their ability and capacity to argue. It is no coincidence that the best political orator of modern times, Barack Obama, has both this sort of background and the intonation of a preacher. Yet this culture of literacy, debate, and access to it has widely declined.

Behind all this lies a real irony – the rejection of intellectualism and elitism belittles the broader population more than the politicians of old did. As Westminster has become more of a bubble and of a game played between those on the inside and in the know, the public has been reduced to a caricature with flint in the bosom and guts in the head. Politicians of the past may have had a patrician streak a mile wide. However, they still respected their audiences enough to explain things properly – combining strong rhetoric and well-developed ideas with clarity. They set out a position and encouraged people to follow, speaking often in simple terms, but using them to clarify complex concepts.

Now, little of this happens. The details of policy are regularly dismissed as “nerd stuff” among commentators who prefer the horse commentary of who is up and down. Politicians follow the audience, or more often a half-imagined version of it, rather than addressing them. More than that, there is an engineered distrust of speaking well or engaging in complex ideas. A false assumption that ease is equivalent to authenticity has taken hold. For all the pushback against elitism, politicians and the media treat citizens as incapable of thought, leaving ideas half-formed, debates shallow, and public life impoverished. It smacks of a lack of respect for the ordinary person, who, ironically, is likely to be better educated than their forebears of the 50s and 60s.

There are other drivers of this, too. Too many in Westminster see the slick, persuasive product of previous successful campaigns and fail to recognise what it resulted from. The messaging and the polling are seen as what matters, not the thinking that lies behind them. The approach is compounded by a bias towards promoting and recruiting those who “do well on Twitter” rather than addressing political challenges. Few want to do the hard work of building a platform that works and selling it, and would rather jump to the last bit.

For MPs themselves, competing demands further disincentivise really getting to grips with problems. The life of parliamentarians now makes it harder to test your ideas. The exponential rise of constituency work and campaigning groups has made it harder for politicians to take the time to wrestle with ideas. The BBC Brown and Blair documentary discusses how the pair would spend hours debating policy and politics in their early days in Westminster. Now, they would be far more focused on bulging inboxes and having photos taken with charity groups. An MP who neglected this would unlikely be saved by their knowledge of how Germany regulates its water companies or tax reform. Once again, smart as MPs may be, the incentives push against intellectualism.

One obvious result has been the decline of political oratory. Speeches have given way to clips for the socials, quotations to memes. Arguably, this does not matter—trends in communication ebb and flow, the world moves on. But it is a secondary effect of a deeper problem. Good speeches are necessarily the result of good thinking: attention to your message, your values, and how every line and word contributes to it. You can only craft them if you are confident in your ideas, which so many politicians now are not. You can, of course, have clarity of thought without producing grand speeches, but we seem to have lost both.

This is more than the loss of memorable quotes. Politics has become so reactive, so consumed by communications, that space for reflection is vanishing. Without time to wrestle with ideas, the ability to think atrophies like an untrained muscle. The political class does not become stupid, but it calcifies—incapable of grappling with complexity, forced into safe generalities, and increasingly adrift on the issues that matter. Decisions are made to survive the news cycle rather than to pursue principle. Policies remain untested, positions unexamined, and arguments shallow.

The consequences ripple beyond parliament. Citizens are left with a half-formed public discourse, unable to see complexity, and politicians who lack conviction or clarity. Leadership without reflection produces ideas without coherence, speeches without weight, and ultimately a politics that fails to lead. The erosion of intellectual habit is not a matter of style—it is a matter of capacity itself. When it declines, the public senses its absence and channels that into further disillusionment.

If politics is to regain confidence and effectiveness, it must reclaim the space for thought. This is not a call for nostalgia or elitism, but for the basic recognition that ideas matter—and that they require work. MPs must be able to test, refine, and defend their positions without fear that nuance will be punished on social media or by soundbite-hungry editors. The media must resist the reflex to reduce debate to a scoreboard, and the public must insist on more than the fleeting excitement of a quote. Quite simply, the incentive structures need to change if behaviour is to change.

We need to regain a culture that prizes clarity of thought as much as clarity of expression, where the rewards for insight are as visible as those for attention. Only then will speeches regain weight, policies regain coherence, and politicians regain the confidence to lead rather than just perform. Whatever your politics, there is no denying we face hard choices and dilemmas ahead. The only way to navigate them is with soundly explored principles, refined into effective policies and knowingly made trade-offs. While politics was never perfect for this, it was certainly better – and fixing it requires rebuilding a system that encourages better behaviour.

And now for something else…

Honestly, I’ve had a few big things going on away from the keyboard, so I haven’t read too much this week. I would, however, recommend this piece on the Georgia protests. Coinciding with the completion of a full calendar year of protests, the BBC have reported on the use of chemical weapons against the demonstrators by the Georgian government. It is shocking and important - especially as it was followed by a crackdown on those who spoke to the BBC.

This explains why the electorate do not grasp trade offs needed for coherent policy making. The electorate as a result just asks for more and more and more…….