On being a sort of Tory

Some personal reflections on politics and the Party

Ever since I posted my first substack and unexpectedly went viral in the world of political commentary, I've been asked one question repeatedly: “Why are you a Conservative?”. Sometimes it has been from neutral curiosity or paired with an implied compliment or insult – whether “but you’re so aware of their failings?” or “how can you be so naïve?”. I’ll admit it is a question that kicked around my own head as I typed out my disillusioned takes on the state of the party.

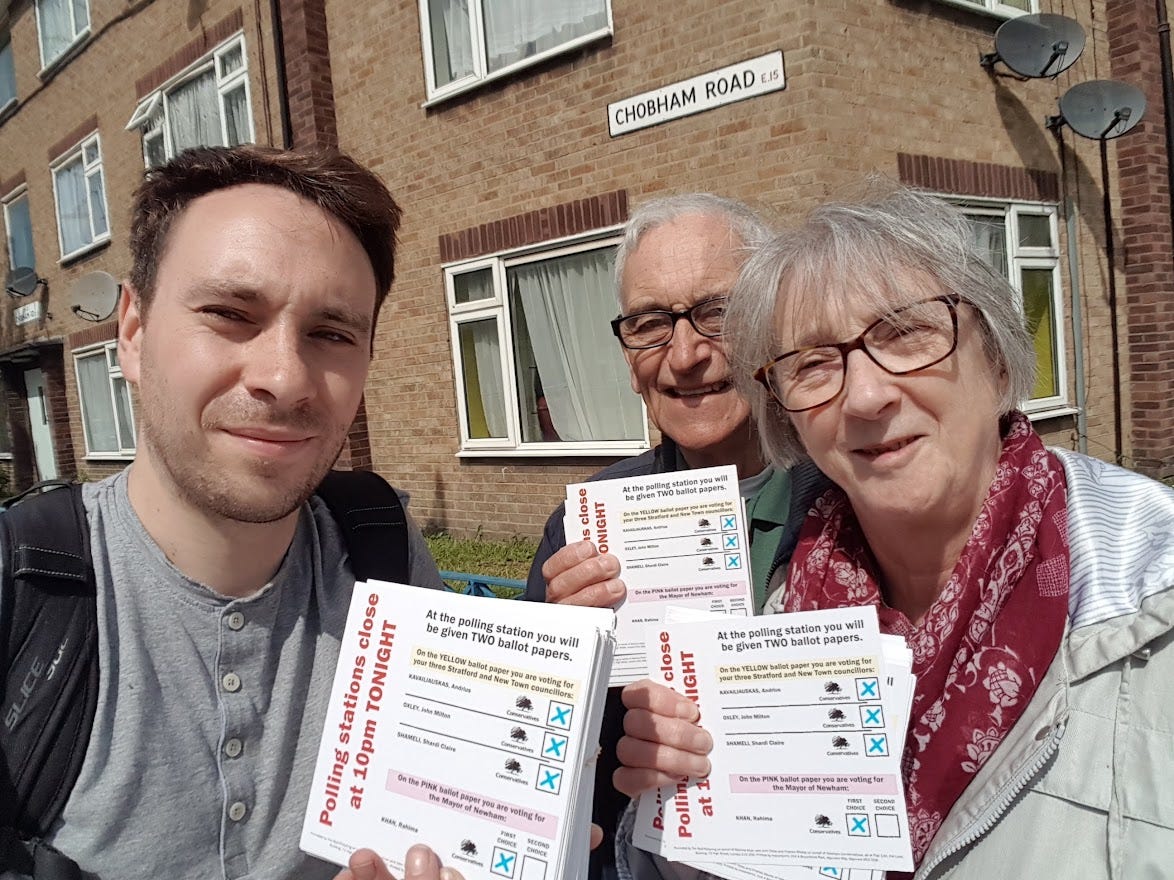

The truth is, I never really consciously decided on my allegiances. Growing up, politics was something that just flowed through the house. My parents had, at various times, been Tory councillors, candidates, and voluntary party officers. I was on the campaign trail before I can even remember, wads of leaflets stuffed into my pushchair for the Langbaurgh by-election.

By the time I was at primary school, spring nights meant electioneering. Where some fathers teach you how to tie a fishing fly or the workings of an engine, mine showed me how to fold a leaflet, how you could spot which council houses had done “right-to-buy” and were more likely to vote blue, and when an “I’ll think about it” on the doorstep meant “maybe” and when it meant “f*ck off”. A strict adherence to the Representation of the People Act meant that my requests for extra-pocket money for helping were rebuffed, but in truth those hours out with my dad were treat enough.

As I grew older, these days of campaigning were accompanied by more complex political discussions. It wasn’t an indoctrination, but a constant elucidation of a world view – a sharing of ideas, a debate. My father’s outlook was different from most of the parents of children I knew. He was older, born towards the end of the war, a product of a different time and vibe. He’d joined the Tories under Macmillan, I think, and his politics were shaped by the fifties and the sixties – whether the horrors of the suppression of the Hungarian Revolution and the Prague Spring, or boon of the economic growth that came under Supermac. While at university he was lectured by Oakeshott and Popper. He was (and is) a conservative in outlook and conviction. Iain Macleod and Airey Neave were as much part of his personal pantheon as Len Hutton and Derek Dooley.

The Conservative Party always in time forgives those who were wrong. Indeed often, in time, they forgive those who were right.

- Iain Macleod

It is perhaps unsurprising that this outlook rubbed off on me. By the time I was old enough to vote, I was a firm supporter of the party, darkening a ballot paper for the first time as soon as I turned 18. Though in a hopeless race, the competition of electoral politics connected with my ambitious psyche, creating an emotional pull. What some boys found in being a centre-forward, I found in being a centre-right candidate.

At university, I joined the Conservative Association and found likeminded friends. Most were far removed from the typical student Tory, caring little for political dogmatism and far more interested in drinks and conversations. Ours was a gentle Toryism, rooted in patriotism and a liberalism tempered with duty, more focused on the longue durée than exactly how the deficit was moving. Several of them remain among my closest friends today.

This time coincided with the 2010 election and the return of Conservative-led government. It was a shift we revelled in, in the same way you revelled in your team winning the cup (so I’m told: as a Sheffield Wednesday supporter, it is a remote dream), but brought with it a new responsibility, of being part of the side who were doing things. Most of the Tories I knew at that point were realistic but unenthusiastic adopters of austerity, believing there was a bloated and inefficient state that spent too much, achieved too little and could do with being trimmed. I don’t think any of us really ever tried to understand how it would be fixed.

After university I drifted in and out of politics before settling in with my local association. Again, this was driven more socially than politically. In the unwinnable depths of East London there was a certain freedom in local campaigning, knowing we were aiming for second place at best, getting the glory from showing up and giving people the chance to vote even if it were unlikely to impact any results. Beyond this, it again offered a good chance to meet like minded people, chat about politics and enjoy each other’s company.

At the same time, being connected with the party became part of my identity – as much in the eyes of others as my own. While I was never quite the Tory Boy of caricature, it was the thing I was known for, the subject of gentle ribbing and probably my most famous trait among my peers. If I hadn’t seen someone for a while, the first thing they’d mention would be politics. It was almost a calling card.

As I grew older, my philosophies fluctuated. I became more interested in policies, more concerned with outcomes. My views aligned with some strains of the party and disagreed with others. I find most of the internal labels of party factions confused and confusing, but broadly speaking I believed in free enterprise delivering prosperity and security to all, a respect for our national story and traditions, and society liberated by personal freedoms but bound by personal duties.

The first real challenge to my attachment to the Tories came in 2016. I supported Remain, a decision driven by both head and heart. Unlike many Conservatives, I believed in the European project and, unlike many Remainers, I saw the EU with its harmonisation of regulations and smoothing of barriers to be an accelerant of European capitalism. I thought Leave offered an incoherent and unachievable exit, one which would be mired in squabbling and would fail in its desire to retain much of the good of membership whilst jettisoning the bad.

It was not however, entirely the result which disillusioned me. For me, Remain vs Leave was always a decision about risk – whether it was worth taking or not. I believed it was not, but saw how others might view it differently. Political questions are not exam, there is not a right or wrong answer which gets revealed the next day. However, what shocked me within the party was the number of people, both senior and junior, who appeared to have a Damascene moment as soon as the result was declared.

While I believed that politically there was no way to undo the result, I could not see how overnight you could pivot from an enthusiastic Remainer to the hardest of Leavers. I watched as some of the more ambitious people I knew on the list of prospective parliamentary candidates purged their social media, making it easier to hide their views from potential selection committees, reinventing themselves as life-long Eurosceptics. MPs made similar about turns in their views in order to boost their careers. It was a rude awakening to the hollowness of the politics of many in the party.

It was in 2019, however, that my relationship with the party fully soured. I was never really a fan of Boris Johnson. He was to me always a liar and a charlatan, a man whose conduct disregarded and harmed almost all of those around him. I never saw him as the politician to share a pint with – he always seemed the type to shirk his round and crudely draw attention to himself. The sort of man you hoped you’d have the courage to punch when the time came. Seeing the leadership handed to someone so deeply unsuited to high office perturbed me, as did the fanatical enthusiasm of his acolytes. I stayed with the party about of spite, not wanting to be driven away, not wanting to give them the satisfaction or the control, and wanting to be there for any subsequent leadership contest.

This sense was compounded by the various scandals that plagued the party under Boris. This is not a place for a full interrogation of his policies, but on a personal level his government fell far short of the mark over and over. Episode after episode showed a self-obsession and self-promotion which jarred with my values. I was shocked how nonchalant most Conservatives seemed to be over Matt Hancock, for example, as if lying to your family, those supposedly closest to you, to get your end away were not in any way worthy of scorn. This feeling deepened as the party descended into the scandal-athon that began with the Owen Paterson report just over a year ago and never quite seemed to end.

The party seemed to have no guiding moral principle, no conscience. Transgression after transgression was defended, lied about, and spun without a hint of contrition, or embarrassment whilst the government failed to address many mounting problems. I mentally drew a line through those I knew in and around the party, between the partisans who would defend anything and those who were clear minded enough to criticise. It was only the latter that retained my respect. The rest had either lost their minds or their dignity.

It threw more light upon my relationship with the Conservatives. I started to realise the real inculcation I had had those long April nights on delivery rounds and canvassing sessions with my father. They had only tangentially been about Conservative Party politics, but instead a broader ethos.

I realised that my dad had really stood for far more than the Conservative Party. His character was rooted firmly in kindness and truth. In his late seventies, he still volunteers for charities and helps those around him. He dutifully followed the covid restrictions because he believed it was the right thing to do. He has a gentle, unostentatious Christian faith, doing good without being a do-gooder. Standing by always ready to help and support those he knows and those he doesn’t. Despite an exterior of being a grumpy-old sod he does his best to embody the little platoons of Burke. He is no longer involved in the Conservative Party.

From that flows a political view – a belief in freedom and individualism not simply to do what is self-interested, but what is right. A hope that left to their own devices, without the overbearing intervention of the state, individuals and communities would flourish. A view founded in the ideals of duty, service, patriotism, but above all kindness. These are values that sometimes entwine with the Conservative Party, and should do when it is at it’s best, but are not owned by it and not always ascribed to by it. I realised, perhaps later than I should, that it was the man I admired, respected, and believed in, not the party.

Now I sit at a strange crossroad. My views more closely align with the traditions of the right than anywhere else. For many reasons I would struggle to subscribe to the left in its historic or modern forms. Equally, though I am disillusioned with what many on the right do and say, repulsed by the nastiness and dishonesty which has no part in my view of Toryism. There is some hope in staying and trying to shape the party – but it is a long fight and one of uncertain victory.

Or perhaps like Ford Madox Ford’s Christopher Tietjens I am now a “Tory of such an extinct type” that the party will never reconcile with me. Only a liar or a moron can wholeheartedly back a political party, there will always be disagreements and concessions. The question is how long those bounds can be stretched before they become untenable. For me, it is a difficult question. The party has been part of my life for all my life, yet at the same time the days of alienation continue to mount.

I suspect that I will always remain a Tory in outlook. The question is whether being part of the Conservative Party will remain a necessary, rewarding, or even compatible part of that. At present, it’s not one I have an entirely satisfactory answer for.

What I do know is that, while the Party has done so much to lose my respect and support, my admiration for my parents and their values is steadfast.

More from me:

The Tories were destined for civil war

In a political crisis, everyone is a potential enemy

Rishi Sunak and the triumph of managerialism

Britain may find that the best option is the most boring and sensible one